Press release

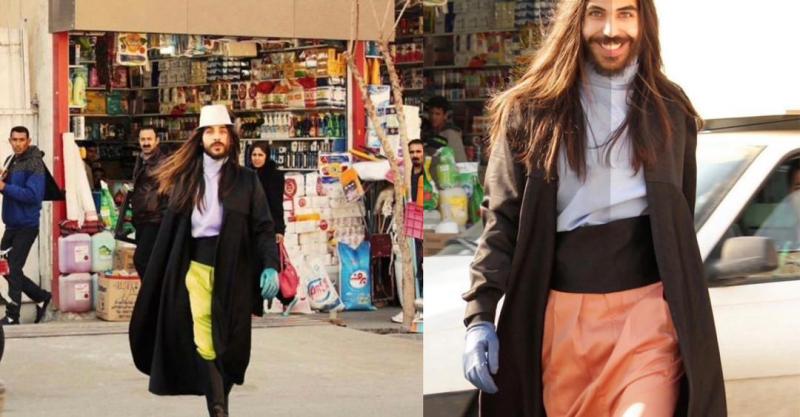

Salar Bil the predecessor of Tehran's conceptual - existence - challenges.

Salar Bil is active in expanding Western art in trends and fashion with important icons in social fields like Duchamp, he has quickly covered the avant-garde artistic movements of his time and communicates with authors and fashion figures by writing articles. He wrote: In David Henry Hwang's Tony award-winning play, M. Butterfly, Broadway audiences encounter a dazzling spectacle, in which a tale of seemingly mistaken gender identities and delusions perpetuated over decades occasions a richly textured production moving in and around the spaces of global politics, gender and racial identities, and the power relations inevitably present in what we call love. A close examination of M. Butterfly has profound implications for our assumptions about identity, including anthropological theories of the self or the person, the ways gender and race are mutually implicated in the construction of identity, and the pervasive insidiousness of gender and racial stereotypes. The story intrigues through its sheer improbability. The playwright's notes cite the New York Times, which in May of 1986 reported the trial of a "former French diplomat and a Chinese opera star" who were "sentenced to six years in jail for spying for China after a two-day trial that traced a story of clandestine love and mistaken sexual identity.... Mr. Bouriscot was accused of passing information to China after he fell in love with Mr. Shi, whom he believed for twenty years to be a woman. In asking himself how such a delusion could be sustained for so long, Hwang takes us through the relations between France and Indochina, and most especially, through the terrain of written images of "the Orient" occupied most centrally by that cultural treasure, Madama Butterfly. These already written images-the narrative convention of "submissive Oriental woman and cruel white man"-are played out in many different arenas, including, perhaps most tellingly, the space of fantasy created and reproduced by the Frenchman himself. An analysis of M. Butterfly suggests the ways Hwang challenges our very notions of words like "truth," our assumptions about gender, and most of all, how M. Butterfly subverts and undermines a notion of unitary identity based on a space of inner truth and the plenitude of referential meaning. Through its use of gender ambiguity present in its very title-is it Monsieur, Madame, Mr., Ms. Butterfly? - through power reversals, through constituting these identities within the vicissitudes of global politics, Hwang conceals, reveals, and then calls into question so-called "true" identity, pointing us toward a reconceptualization of the topography of "the self." Rather than a bounded essence, filled with "inner truth," separated from the world or "society" by an envelope of skin, M. Butterfly opens out the self to the world, softening or even dissolving those boundaries, where identity becomes spatialized as a series of shifting nodal points constructed in and through fields of power and meaning.Salar Bil continued : Finally, M. Butterfly intertwines geography and gender, where East/West and male/female become mobile positions in a field of power relations. It suggests that analyses of shifting gender identity must also take into account the ways gender is projected onto geography, and that international power relations and race are also, inevitably, inscribed in our figurations of gender. Perhaps the creative subversiveness of Hwang's play best emerges in contrast to the conventions of the opera Madama Butterfly, to which it provides ironic counterpoint. This cultural "classic"-music by Giacomo Puccini, libretto by Giuseppe Giacosa and Luigi Illica, based on a story by John Luther Longdebuted at La Scala in 1904. It remains a staple of contemporary opera company repertoire, one of the ten most performed operas around the world. As we will see, Hwang reappropriates the conventional narrative of the pitiful Butterfly and the trope of the exotic, submissive Oriental woman, rupturing the seamless closure and the dramatic inevitability of the story line. The conventional narrative, baldly stated, goes something like this. Lieutenant Benjamin Franklin Pinkerton is an American naval officer, stationed on the ship Abraham Lincoln in Nagasaki during the Meiji period, the tum of the century when Japan was "opened" to the West. The opera begins with Pinkerton and Goro, a marriage broker, as they look over a house Pinkerton will rent for himself and his bride-to-be, a fifteen-year-old geisha named Cho-Cho-san ("butterfly" in Japanese). American consul Sharpless arrives, and Pinkerton sings of his hedonistic philosophy of life, characterizing himself as a vagabond Yankee who casts his anchor where he pleases. "He doesn't satisfy his life/if he doesn't make his treasurelthe flowers of every region...the love of every beauty.,, Pinkerton toasts his upcoming marriage by extolling the virtues of his open-ended marriage contract: "So I'm marrying in the Japanese way/for ninehundred-ninety-nine yearslFree to release myself every month" (189). Later, he toasts "the day when I'll marry/ln a real wedding, a real American wife" (191). When Butterfly arrives with an entourage of friends and relatives, Pinkerton and Sharpless discover that among the treasures Butterfly carries with her into her new home is the knife her father used for his seppuku, or ritual suicide by disembowelment-and music foreshadows the repetition that will inevitably occur. Friends and relatives sing their doubts about the marriage, and in a dramatic moment, Butterfly's uncle, a Buddhist priest, enters to denounce her decision to abandon her ancestors and adopt the Christian religion. Rejected by her relatives, Butterfly turns to Pinkerton. The couple sing of their love, but Cho-chosan expresses her fear of foreign customs, where butterflies are "pierced with a pin" (215). Pinkerton assures her that though there is some truth to the saying, it is to prevent the butterfly from flying away. They celebrate the beauty of the night. "All ecstatic with love, the sky is laughing" (215), says Butterfly as they enter the house and Act One closes. By the beginning of Act Two, Pinkerton has been gone for three years. Though on the verge of destitution, Butterfly steadfastly awaits the return of her husband, who has promised to come back to her "when the robin makes his nest" (219). And, known only to her servant, Suzuki, Cho-cho-san has had a baby, a son with occhi azzurini, "azure eyes," and i ricciolini d'oro schietto, "little curls of pure gold"-truly a stunning genetic feat. The consul Sharpless comes to call, bearing a letter from Pinkerton, and he informs Butterfly that her waiting is in vain, that Pinkerton will not return and that she should accept the marriage proposal of the Prince Yamadori who has come to court her. Still sure of her husband, she will have none of it. In Cho-cho-san's eyes, she is no longer Madame Butterfly, but Mrs. Pinkerton, bound by American custom. In desperation, hoping the consul will persuade Pinkerton to return, Cho-Cho-san brings out her son. At that point Pinkerton is in fact already in Nagasaki with his American wife. Knowing that he is in port, Butterfly and Suzuki decorate the house with flowers, and Butterfly stays awake all night, awaiting Pinkerton's arrival. In the morning, when Suzuki finally persuades her mistress to rest, Sharpless and Pinkelton arrive. Pinkerton has decided to claim his son and raise the boy in America, and he persuades Suzuki to help him convince Butterfly that this is for the best. Later, Cho-cho-san sees Sharpless and an American woman in the garden. Now, realizing that Pinkerton has in fact married again, Cho-cho-san cries out with pain, "All is dead for mel/All is finished, ahl" (253) and she prepares for the inevitable. She tells Sharpless to come with Pinkerton for the child in half an hour. Cho-cho-san unsheathes her father's dagger, but then spies her son, whom Suzuki has pushed into the room. In her agony, the music forces her higher and higher, as her voice threatens to soar out of control and then sinks to an ominous low note. Cho-cho-san blindfolds her child, as if to play hide-and-seek, goes behind a screen to insert the knife and emerges, staggering toward the child. The brass section accompanies her death agony, trumpeting vaguely Asiansounding music until finally, climactically, a gong signals her collapse. We hear Pinkerton's cries of "Butterflyl" as Pinkerton and Sharpless run into the room. Butterfly points to the child as she dies, and the opera resolves in a swelling, tragic orchestral crescendo. In Madama Butterfly Puccini draws on and recirculates familiar tropes: the narrative inevitability of a woman's death in operas and most especially, the various markers of Japanese identity: Butterfly as geisha, that quintessential Western figuration of Japanese woman, the manner of Butterfly's death, by the knife-the form of suicide conventionally associated in the West with Japan, the construction of the Japanese as a "people accustomed/to little things/humble and silent" (213). And little is exactly what Butterfly gets. In Western eyes, Japanese women are meant to sacrifice, and Butterfly sacrifices her "husband," her religion, her people, her son, and ultimately, her very life. The beautiful, moving tragedy propels us toward narrative closure, as Butterfly discovers the truth-that she is, indeed, condemned to die as her identity as a Japanese geisha demands-an exotic object, a "poor little thing," as Kate Pinkerton calls her. In Puccini's opera, men, women, Japanese, Americans, are all defined by familiar narrative conventions. And the predictable happens: West wins over East, Man over Woman, White over Asian. The music, with its soaring arias and bombastic orchestral interludes, amplifies the points and draws us into further complicity with convention. Butterfly is forced into tonal registers that edge into a realm beyond rational control, demanding a resolution which arrives, (porno)graphically, with the crash of the gong. Music and text collaborate, to render inevitable this tragic-but oh-so-satisfying denouement: Butterfly, the little Asian woman, crumpled on the floor. The perfect closure. Identities, too, are unproblematic entities in Puccini's opera; indeed, Puccini reinforces our own conventional assumptions about personhood. Butterfly's attempts to blur the boundaries and to claim for herself a different identity-that of American-are doomed to failure. She is disowned by her people, and she cleaves to Pinkerton, reconstituting herself as American, at least in her own eyes. But the opera refuses to allow her to "overcome" her essential Japanese womanhood. The librettists have Butterfly say things and do things that reinforce our stereotyped notions of the category "Japanese woman": she is humble, exotic, a plaything. Pinkerton calls her a diminutive, delicate "flower," whose "exotic perfume" (199) intoxicates him. His bride, this child woman with "long oval eyes" (213), makes her man her universe. And like most Japanese created by Westerners, Butterfly is concerned with "honor" and must kill herself when that honor has been sullied. Death, too, comes in the stereotypical form. Her destiny is to die by the knife metaphorically, via sexual penetration, and finally, in her ritual suicide. Butterfly is defined by these narrative conventions; she cannot escape them. Dorinne Kondo would suggest that this view of identity-a conventional view familiar to us in our everyday discourses and pervasive in the realm of aesthetic production-is based on a particular presupposition about the nature of identity, what philosophers call "substance metaphysics."Identities are viewed as fixed, bounded entities containing some essence or substance, expressed in distinctive attributes. Thus Butterfly is defined by attributes conventionally associated in Western culture with Asian--or even worse, "Oriental"-women. Furthermore, Kondo argues that a similar view of identities underlies the burgeoning anthropological literature on what we call the self or the person. "The self" carries a highly culturally specific semantic load and presents apicture of unitary totality. According to our linguistic and cultural conventions, "self' calls up its opposing term, "society," and presupposes a particular topography: a self, enclosed in a bodily shell, composed of an inner essence associated with truth and real feelings and identity, standing in opposition to a world that is spatially and ontologically distinct from the self. A self is closed, fixed, an essence defined by attributes. Typically, the many anthropological analyses of La notion de personne, the concept of self in this or that culture, abstract from specific contexts certain distinctive traits of the self among the Ilongot, the Ifaluk, the Tamils, the Samoans, the Americans. And even those analyses which claim to transcend an essentialist notion of identity and a self/society distinction by arguing for the cultural constitution of that self tend to preserve the distinction in their rhetoric. That one can even talk of a concept of self divorced from specific historical, cultural, and political contexts privileges the notion of some abstract essence of selfhood we can describe by enumerating its distinctive features. This self/society, substance/attribute view of identity underlies anthropological narratives just as it informs aesthetic productions like Madama Butterfiy. The self/society, subject/world tropes insidiously persist m a multiplicity of guises in the realms of theory and literature, but in anthropology, the literature on the self has transposed this opposition into another key: the distinction between a person-a human being as bearer of social roles-and self-the inner, reflective essence of psychological consciousness, recapitulating the binary between social and psychological, world and subject. Yet anthropology deconstructs this binary even as it maintains its terms, for in demonstrating the historical and cultural specificity of definitions of the person or the self, we are led to a series of questions: Are the terms "self' and "person" the creations of our own linguistic and cultural conventions? If "inner" processes are culturally conceived, their very existence mediated by cultural discourses, to what extent can we talk of "inner, reflective essence" or "outer, objective world" except as culturally meaningful, culturally specific constructs? And how is the inner/outer distinction itself established as the terms within which we must inevitably speak and act? Early studies of the person, like the classic Marcel Mauss essay, take as a point of departure La notion de personne as an Aristotelian category, an example of one of the fundamental categories of the human mind. Traversing space and time, Mauss draws our attention to different ways of defining persons and selves in different cultures in different historical moments, but posits the evolutionary superiority of Western notions of the same. In a key passage, Mauss discusses the notion of the self: Far from existing as the primordial innate idea, clearly engraved since Adam in the innermost depths of our being, it continues here slowly, and almost right up to our own time, to be built upon, to be made clearer and more specific, becoming identified with self-knowledge and the psychological consciousness. Western conceptions of self as psychological consciousness and a reflexive selfawareness, based on a division between the inner space of selfhood and the outer world, are held up as the highest, most differentiated development of the self in human history. Though Mauss's insights have been elaborated in richly varied ways, most anthropological analyses leave in place the rhetoric of the self as psychological consciousness and self-knowledge, continuing to impart the impression of implicit ethnocentric superiority, essential unity, and referential solidity. Kondo has used the term "referential solidity," for it is clear that this rhetoric/ theory of the self pivots around a spatialized ideology of meaning as reference. Saussure's influential formulation of the sign as the relation between signifier (the sound-image, "the impression it makes on our senses") and signified (the concept inside the head, "the psychological imprint of the sound"), links the speaking subject to assumptions about meaning as plenitude, a fullness occupied by certain contents, located inside the self. Here we find another permutation of the Cartesian dichotomy between reason and sense perception. Self is constituted culturally, but in its presence, supported by the solidity of referential meaning, "the self" takes on the character of an irreducible essence, the Transcendental Signified, a substance which can be distilled out from the specificities of the situations in which people enact themselves. Such an essence of inner selfhood preserves the boundaries between the inner space of true selfhood and the outer space of the world. The many anthropological accounts reliant on characterizations of la notion de personne, "the concept of self," with no reference to the contradictions and multiplicities within "a" self, the practices creating selves in concrete situations, or the larger historical, political, and institutional processes shaping those selves, decontextualize and reify an abstract notion of essential selfhood, based on a metaphysics of substance. Echoing Madama Butterfly's familiar narrative conventions and satisfying sense of closure, anthropological narratives recirculate tropes of a self/world boundary and a substance/attribute configuration of identity. However, when we move from the conventions of fixed, essentialist identities in Madama Butterfly to the subversion of those conventions in M. Butterfly, we might go on to ask how selves in the plural are constructed variously in various situations, how these constructions can be complicated and enlivened by multiplicity and ambiguity, and how they shape and are shaped by relations of power. Such an approach would open out the space of selfhood to the world, dissolving the boundaries and emptying the inner self of its plenitude, spatializing selves as conjunctions of forces produced by history, politics, culture, and narrative conventions, within a changing, complicated, and open discursive field. From clear boundaries between inner and outer, fixed identities characterized by distinctive attributes, and narrative closure to an open, shifting multiplicity of meanings, constituted in and by a changing field of discourses and forces of power, where selves in the plural are empty of reference in an essentialist sense: these are the moves suggested by an analysis of David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly. The play opens with ex-diplomat Rene Gallimard in prison. (His last name, the name of a famous French publishing house, already resonates with notions of narrative and of textual truth, and his first name, which sounds the same in its masculine and feminine forms, underlines the theme of gender ambiguity). "It is an enchanted space I occupy" (8), he announces, and indeed, it is enchanted-a space of fantasy, a prison of cultural conventions and stereotypes where Gallimard's insistence on reading a complex, shifting reality through the Orientalist texts of the past make him the prisoner and eventually, the willing sacrificial victim of his own culturally and historically produced conventions. Gallimard will be seduced, deluded, imprisoned by clinging to an ideology of meaning as reference and to an essentialist notion of identity. For him, clichéd images of gender and of race and geography unproblematically occupy the inner space of identity, enabling opera star Song Liling to seduce him through the play of inner truth and outer appearance. The first encounter between Song and Gallimard occurs in a performance at the home of an ambassador, where Song plays the death scene from Madama Butterfly. Clothed as a Japanese woman, wearing a woman's makeup, Song is "believable" as Butterfly. This "believability" occurs on the planes of gender, size, and geography, when Gallimard gushes to Song about her/his wonderful performance, so convincing in contrast to the "huge women in so much bad makeup" (18) who play Butterfly in the West. Gallimard adheres to stereotyped images of women and of the Orient, where he assumes a transparent relationship between outer appearance and the inner truth of self. The signs of this identity are clothing and makeup, and since Song is dressed as a woman, Gallimard never doubts Song's essential femininity. Gallimard's equally essentialized readings of the Orient enable Song to throw Gallimard off balance with herlhis initial boldness, when s/he describes the absurdity of Madama Butterfly's plot, but for the geographic and racial identities of its protagonists: Consider it this way: what would you say if a blonde homecoming queen fell in love with a short Japanese businessman? He treats her cruelly, then goes home for three years, during which time she prays to his picture and turns down marriage from a young Kennedy. Then, when she learns he has remarried, she kills herself. Now, I believe you would consider this girl to be a deranged idiot, correct? But because it's an Oriental who kills herself for a Westerner-ah!-you find it beautiful (18). Later, Song becomes flirtatious, and strategically exhibits the appropriate signs of her inner, essential Oriental female self: modesty, embarrassment, timidity. Gallimard responds, "I know she has an interest in me. I suspect this is her way. She is outwardly bold and outspoken, yet her heart is shy and afraid. It is the Oriental in her at war with her Western education" (25). Thus, Gallimard reads Song's Westernized, masculine exterior as mere veneer, masking the fullness of the inner truth of Oriental womanhood. However she may try to alter this substance of identity, in Gallimard's eyes, she-like Madame Butterfly-will never be able to overcome her essential Oriental nature. This conventional reading of identity enables Song to manipulate the conventions to further herlhis ends, to become more intimate with Gallimard, and eventually, to pass on to the government of the People's Republic of China the diplomatic secrets slhe learns in the context of their relationship. When Song first entertains Gallimard in herlhis apartment, Slhe appeals to Orientalist stereotypes of tradition, modesty, unchanging essence, invoking China's twothousand-year history and the resulting significance of her actions: "Even my own heart strapped inside this Western dress ... even it says things.... things I don't care to hear" (27). Her/his appeal finds a willing audience in Gallimard, who finds this Song far more to his liking, and shares with the audience his delighted discovery that "Butterfly," as he has begun to call her, feels inferior to Westerners. Seeing Song supposedly revealed-paradoxically, in the moment of her greatest concealment-in her feminine/Oriental inferiority, behaving with appropriate submissiveness and docility, Gallimard for the first time finds what he believes to be his true self, as a Real Man defined in opposition to Song. Wondering whether his Butterfly, like Pinkerton's, would "writhe on a needle" (28), he refuses to respond to her increasingly plaintive missives, and for the first time feels "that rush of power-the absolute power of a man" (28), as he cleans out his files, writes a report on trade, and otherwise enacts confident masculine mastery in the world of work. In the phrase "the absolute power of a man," Hwang highlights the connection between this power and the existence of a symmetrical but inverted opposite, for though presumably Gallimard was by most people's definitions a man before he met his Butterfly, he can only acquire the "absolute power of a man" in contrast to her. In love with his own image of the Perfect Woman and therefore with himself as the Perfect Man, Gallimard reads signs of dissimulation-that Song keeps her clothes on even in intimate moments, with appeals to her "shame" and "modesty"-as proofs of her essential Oriental womanhood. In so doing, he guards his inner space of "real, masculine" identity. Gallimard begins with a conception of gender and racial identity based on an ideology of the inner space of selfhood. The audience, however, is allowed a rather different relationship between inner truth and outward appearance, one that initially preserves the distinction between real, inner self and outer role. That Song is a Chinese man playing a Japanese woman is a "truth" we know from an early stage. Song plays ironically with this "truth" throughout. Its subtleties are powerfully articulated in a scene where Song is almost unmasked as a man. Gallimard, humiliated by the failure of his predictions in the diplomatic arena, demands to see his Butterfly naked. Song, in a brilliant stroke, realizes that Gallimard simply desires her to submit. S/he lies down, saying, "Whatever happens, know that you have willed it ... I'm helpless before my man" (47). Gallimard relents, and Song wins. Later, Song triumphantly recounts the crisis to Comrade Chin, the PRC emissary and then rhetorically asks her: "Why, in the Peking opera, are women's roles played by men?" Chin replies, "I don't know. Maybe, a reactionary remnant of male..." Song cuts her off. "No. Because only a man knows how a woman is supposed to act" (49). Irony animates these passages. On the one hand, Song is surely a man playing a woman-and his statement is a clear gesture of appropriation. However, Hwang suggests that matters are more complicated, that "woman" is a collection of cultural stereotypes connected tenuously at best to a complex, shifting reality. Rather than expressing some essential gender identity, full and present, "woman" is a named location in a changing matrix of power relations, defined oppositionally to the name "man." So constructed by convention and so oppositionally defined is woman, that according to Song, only a man really knows how to enact woman properly. And because man and woman are oppositionally defined terms, reversals of male and female positions are possible. Indeed, it is at the moment of his greatest submission/humiliation as a woman that Song consolidates his power as a man. S/he puts herself "in the hands of her man," and it is at that moment that Gallimard relents-and feels for the first time the twinges of love, even adoration. The vicissitudes of the Cultural Revolution and the signal failure of Gallimard's foreign-policy predictions send Gallimard home to France, but he keeps a shrine-like room waiting for his Perfect Woman. And in his devoted love, his worship of this image of Perfect Woman, Gallimard himself becomes like a woman. A dramatic reversal is effected in the play in Act Three through a stunning confrontation, where Song reveals his "manhood" to Gallimard. By this time Song is dressed as a man, but he strips in order to show Gallimard his "true" self. Gallimard, facing Song, is convulsed in laughter, finding it bitterly amusing that the object of his love is "just a man" (65). Song protests in an important passage that he is not "just a man," and tries to persuade Gallimard that underneath it all, it was always him-Song-in his full complexity. Gallimard will not be persuaded, however. Clinging to his beloved stereotypes of Oriental womanhood, now supposedly knowing the difference between fantasy and reality, he declares his intention to "choose fantasy" (67). Song announces his disappointment, for his hope was for Gallimard to "become... something more. More like ... a woman" (67). Song's efforts are to no avail, and Gallimard chases Song from the stage. Gallimard returns to his prison cell in a searing finale and launches into a chilling speech as he paints his face with geisha-like makeup and dons wig and kimono. He speaks of his "vision of the Orient" (68), a land of exotic, submissive women who were born to be abused. He continues: ... the man I loved was a cad, a bounder. He deserved nothing but a kick in the behind, and instead I gave him ... all my love. Yes-love. Why not admit it all. That was my undoing, wasn't it? Love warped my judgment, blinded my eyes, rearranged the very lines on my face ... until I could look in the mirror and see nothing but ... a woman (68). Gallimard grasps a knife and assumes the seppuku position, as he reprises lines from the Puccini opera: Death with honor is better than life ... life with dishonor (68). He continues: The love of a Butterfly can withstand many things ... unfaithfulness, loss, even abandonment. But how can it face the one sin that implies all others? The devastating knowledge that, underneath it all, the object of her love was nothing more, nothing less than ... a man. It is 1988. And I have found her at last. In a prison on the outskirts of Paris. My name is Rene Gallimard-also known as Madame Butterfly (68, 69). Gallimard plunges the knife into his body and collapses to the floor. Then, the coup de grace. A spotlight focuses dimly on Song, "who stands as a man" (69) atop a sweeping ramp. Tendrils of smoke from his cigarette ascend toward the lights, and we hear him say "Butterfly?" as the stage darkens. This stunning gender/racial power reversal forces the audience toward a fundamental reconceptualization of the topography of identity. "True" inner identity is played with throughout, then seemingly preserved in the revelation of Song's "real" masculinity, then again called into question with Gallimard's assumption of the guise of Japanese woman. Whereas the death of Madame Butterfly in Puccini's opera offers us the satisfaction of narrative closure, Gallimard's assumption of the identity of a Japanese woman is radically disturbing, for in this move Hwang suggests that gender identity is far more complicated than reference to an essential inner truth or external biological equipment might lead us to believe. As Foucault has noted, sex as a category gathers together a collection of unrelated phenomena in which male and female are defined oppositionally in stereotyped terms and posits this discursively produced difference as natural sexual difference. M. Butterfly deconstructs that naturalness, opening out the inner spaces of true gender identity to cultural and historical forces, where identity is not an inner space of truth but a location in a field of shifting power relations. Perhaps what Hwang might further emphasize is the inadequacy of either gender category to encompass a paradoxical and multiplicitous reality. The key statement here is Song's, that he is more than "just a man." In the stage directions, Song at the end "stands as a man" (69) in the clothing and the confident, powerful guise of a man. But we cannot say with certainty that he is a man, for man is an historically, discursively produced category which fails to accommodate Song's more complex experience of gender and subverts that ontological claim. Song attempts to persuade Gallimard to join him in a new sort of relationship, where Song is more like a man, Gallimard more like a woman. At precisely this point Hwang suggests the inability of the categories of man and woman to account for the multiple, changing, power-laden identities of his protagonists. Gallimard refuses, saying that he loved a woman created by a man, and that nothing else will do. Song thereupon accuses him of too little imagination. Gallimard immediately retorts that he is pure imagination, and on one level, he is right. In his obsession with the Perfect Oriental Woman, he truly remains the prisoner and then the willing sacrificial victim of his Orientalist cultural cliches-a realm of pure imagination indeed. But this distinction between imagination and reality itself (e.r.e.c.t.s) the bar between categories and fails to open those mutually exclusive spaces to irony, creativity, and subversion. The last word rests with Song, and in the end, his interpretation prevails: that Gallimard has too little imagination to accept the complexity and ambiguity of everyday life, too little imagination to open himself to different cultural possibilities, blurred boundaries, and rearrangements of power. One might also argue that Gallimard's refusal arises from his attempt to keep e.r.e.c.t his boundaries as a heterosexual man. Gallimard's lack of imagination appears in part to be a homophobic retreat, and there is a level at which Hwang seems to suggest that g.ay relationships offer the greatest potential for gender subversion. Yet, upon inquiry, Hwang further complicates matters by refusing us the comfort of conventional binaristic categories: To me, this is not a 'g.zay' subject because the very labels heterosexual or homosexual become meaningless in the context of this story. Yes, of course this was literally a homosexual affair. Yet because Gallimard perceived it or chose to perceive it as a heterosexual liaison, in his mind it was essentially so. Since I am telling the story from the Frenchman's point of view, it is more specificially about 'a man who loved a woman created by a man.' To me, this characterization is infinitely more useful than the clumsy labels 'g.ay' or 'straight.'Hwang once again forces us to confront the pervasive, essentialist dualisms in our thinking and argues instead for historical and cultural specificity that would subvert the binary. Literary critics and readers of French literature will note the striking parallels between the tale of M. Butterfly and the Balzac short story, "Sarrasine," the object of Roland Barthes's S/Z and of Barbara Johnson's essay, "BartheS/BaIZac."Both Sarrasine and Gallimard commit the same errors of interpretation in pursuing their objects of desire. Sarrasine, a sculptor, falls in love with an Italian opera singer, his image of the perfect woman. But La Zambinella is a castrato. Sarrasine, a newcomer to Italy, is ignorant of this custom, and he pays for his ignorance, his passion, and his misinterpretation with his life, victim to the henchmen of the powerful Cardinal who is La Zambinella's protector. Gallimard and Sarrasine are almost perfect mirrors for one another. Signs of beauty and timidity act as proofs to both men that the objects of their love are indeed women. Both flee strong women. In Gallimard's case, this takes the form of escape via a brief affair with another refraction of himselflhis fantasy, a young Western blonde also named Renee, who enacts a symbolic castration by commenting on his "weenie" and advancing her theory of how the world is run by men with "pricks the size of pins." But for Gallimard as for Sarrasine, "it is for having fled castration" (175) that they will be castrated. Both men are unmanned as the world laughs at their follies. And both are undone by their view of gender as symmetrical inversions of mirrored opposites. For both, their own masculinity is defined in contrast to a perfect woman who is a collection of culturally conventional images, and each crafts the Other to conform to those conventions. Neither Gallimard nor Sarrasine is capable of really recognizing another, for in their insistence on clinging to their cherished stereotypes, both love only themselves. In both cases, the truth kills. Clearly, the parallels are stunning. But Hwang does not allow us to stop there. Like these literary critics, Hwang offers us a provocative reconsideration of the construction of gender identity as an inner essence. But for him, a challenge to logocentric notions of voice, of referentiality, of identity as open and undecidable, is only a first step. Hwang opens out the self, not to a free play of signifiers, but to a play of historically and culturally specific power relations. Through the linkage of politics to the relationship between Song and Gallimard, Hwang leads us toward a thoroughly historicized, politicized notion of identity, not understandable without reference to narrative conventions, global power relations, gender, and the power struggles people enact in their everyday lives. These relations constitute the spaces of gender, but equally important, the spaces of race and imperialism played out on a world stage. A double movement is involved here. As Hwang deploys them, Song's words open out the categories of the self and the personal or private domain of love relationships to the currents of world historical power relations. Simultaneously, Hwang associates gender and geography, showing the Orient as supine, penetrable, knowable in the intellectual and the carnal senses. The play of signifiers of identity is not completely arbitrary; rather it is overdetermined by a constitutive history, a history producing narrative conventions like Madama Butterfly. Hwang effects this double movement and plays with the levels of personal and political by situating Gallimard and Song historically, during the era of the Vietnam War and the Cultural Revolution, taking them up to the present. In so doing, he draws parallels between the relations of Asian woman and Western man and of Asia and the West. Act One ends by intertwining these two levels, as Gallimard's triumph in the diplomatic arena-his promotion to vice-consul-coincides with his "conquering" of Song. Act Two continues these parallels, as Song appeals to Gallimard's Orientalism in order to further hislher spying activities for the People's Republic. Extolling the progressiveness of France and exclaiming over hislher excitement at being "part of the society ruling the world today" (36), Song cajoles Gallimard into giving himlher classified information about French and American involvement in Vietnam. In his work, Gallimard uses his new-found masculine confidence and power and the opinions of Orientals he forms in his relationship with Song to direct French foreign policy. We reencounter in the diplomatic arena the exchange of stereotypes pervading the relationship between Gallimard and his Butterfly. ''The Orientals simply want to be associated with whoever shows the most strength and power"; "There's a natural affinity between the West and the Orient"; "Orientals will always submit to a greater force" (37). Not surprisingly, Gallimard's inability to read the complexities of Asian politics and society leads to failure. Gallimard's predictions about Oriental submission to power are proved stunningly wrong during the Vietnam War: "And somehow the American war went wrong too. Four hundred thousand dollars were being spent for every Viet Cong killed, so General Westmoreland's remark that the Oriental does not value life the way Americans do was oddly accurate." "Why weren't the Vietnamese people giving in? Why were they content instead to die and die and die again?" (52, 53). And as the political situation in China changes, so does the relationship between Gallimard and Song change. Gallimard is sent home to Paris for his diplomatic failures; Song is reeducated and sent to acommune in the countryside as penance for hislher decadent ways. Act Three begins with Song's transformation into a man, as he removes his makeup and kimono on stage, revealing his masculine self. It is a manhood based on a collection of recognizably masculine conventions: an Armani suit; a confident stance, with feet planted wide apart, arms akimbo; a deeper voice; a defiant, cocky manner as he strides back and forth on the stage, surveying the audience. He brings together the threads of gender and global politics in a French court. Questioned by a judge about his relationship with Gallimard, Song offers as explanation his theory of the "international r.ape mentality": "Basically, her mouth says no, but her eyes say yes. The West b elieves the East, deep down, wants to be dominated... You expect Oriental countries to submit to your guns, and you expect Oriental women to be submissive to your men" (62). And then Song links this mentality to Gallimard's twenty-year attachment 46 to Song as a woman: "...when he finally met his fantasy woman, he wanted more than anything to believe that she was, in fact, a woman. And second, I am an Oriental. And being an Oriental, I could never be completely a man" (62). Thus, Hwang-in a move suggestive of Edward Said's Orientalism-explicitly links the construction of gendered imagery to the construction of race and the imperialist mission to colonize and dominate. Asia is gendered, but gender in tum cannot be understood without the figurations of race and power relations that inscribe it. In this double movement, M. Butterfly calls into question analyses of race and colonialism which ignore links to gender, just as it challenges theories of gender which would ignore the cultural/racial/global locations from which they speak. In M. Butterfly, gender and global politics are inseparable. The assumption that one can privilege gender, in advance, as a category, setting the terms of inclusion without fully considering those for whom gender alone fails to capture the multiplicity of experience, is itself an Orientalist move. M. Butterfly would lead us to recognize that if the Orient is a woman, in an important sense women are also the Orient, underlining the simultaneity and inextricability of gender from geographic, colonial, and racial systems of dominance. And this is the "critical difference" between the implications of an M. Butterfly, on the one hand, and on the other, deconstructive analyses of gender identity. For Hwang, the matter surpasses a simple calling into question of fixed gender identity, where a fixed meaning is always deferred in a postmodem free play of signifiers. He leads us beyond deconstructions of identity as Voice, Logos, or the Transcendental Signified, beyond refigurations of identity as the empty sign, or an instantiation of "writing inhabited by its own irreducible difference from itself" (Johnson II). And the difference lies in his opening out of the self, not to a free play of signifiers but to a power-sensitive analysis that would examine the construction of complex, shifting selves in the plural, in all their cultural, historical, and situational specificity. In sum, M. Butterfly enacts what I take to be a number of profoundly important theoretical moves for those engaged in cultural politics. It subverts notions of unitary, fixed identities, embodied in pervasive narrative conventions such as the trope of "Japanese woman as Butterfly." Equally, it throws into question an anthropological literature based on a substance-attribute metaphysics which takes as its foundational point of departure a division between self and society, subject and world. M. Butterfly suggests to us that an attempt to exhaustively describe and to rhetorically fix a concept of self abstracted from power relations and from concrete situations and historical events, is an illusory task. Rather, identities are constructed in and through discursive fields, produced through disciplines and narrative conventions. Far from bounded, coherent, and easily apprehended entities, identities are multiple, ambiguous, shifting locations in matrices of power. Moreover, M. Butterfly suggests that gender and race are mutually constitutive in the play of identities; neither gender nor race can be accorded some a priori primacy over the other. Most important, they are not incidental attributes, accidents ancillary to some primary substance of consciousness or rationality that supposedly characterize a self. In M. Butterfly, we find a nuanced portrayal of the power and pervasiveness of gender and racial stereotypes. Simultaneously, Hwang de-essentializes the categories, exploding conventional notions of gender and race as universal, ahistorical essences or as incidental features of a more encompassing, abstract concept of self. By linking so-called individual identity to global politics, nationalism, and imperialism, Hwang makes us see the cross-cutting and mutually constitutive interplay of these forces on all levels. M. Butterfly reconstitutes selves in the plural as shifting positions in moving, discursive fields, played out on levels of so-called individual identities, in love relationships, in academic and theatrical narratives, and on the stage of global power relations. Finally, perhaps we can deploy the spatial metaphor once more, to place M. Butterfly in a larger context and to underline its significance. The play claims a narrative space within the central story for Asian Americans and for other people of color. Never before has a dramatic production written by an Asian American been accorded such mainstream accolades: a long run on Broadway; a planned world tour; Tonys and Drama Desk Awards for both Hwang and B. D. Wong, who played Butterfly; a nomination for the Pulitzer Prize. As an Asian American woman, M. Butterfly is a voice from the Borderlands, to use a metaphor from Gloria Anzaldua and Carolyn Steedman, a case of the "other speaking back,,, to borrow Arlene Teraoka's phrase. Hwang's distinctively Asian American voice reverberates with the voices of others who have spoken from the borderlands, those whose stories cannot be fully recognized or subsumed by dominant narrative conventions, when he speaks so eloquently of the failure to understand the multiplicity of Asia and of women. "That's why," says Song, "the West will always lose in its encounters with the East," and his words seem especially resonant given the history of the post-World War II period, a history including the Vietnam War and the economic rise of Asia. The future Hwang suggestively portrays is one where white Western man may become Japanese woman, as power relations in the world shift and as the West continues to perceive the East in terms of fixity and essentialist identity. And, when Gallimard's French wife laments Chinese inability to hear Madama Butterfly as simply a beautiful piece of music, Hwang further suggests that his own enterprise, and perhaps by extension, ours, requires a committed, impassioned linkage between what are conventionally defined as two separate spaces of meaning, divided by the bar: aesthetics and politics. Those like Gallimard who seek to keep the bars e.r.e.c.t run the risk, Hwang implies, of living within the prison of their culturally and discursively produced assumptions in which aesthetics and politics, the personal and the political, woman and man, East and West form closed, mutually exclusive spaces where one term inevitably dominates the other. It is this topography of closure M. Butterfly-by its very existence-challenges.

Street 1451 Woodruff Rd

City/Town Greenville

State/Province/Region South Carolina

Zip/Postal Code 29607

Phone Number (864) 254-0318

Country United States

Publishing agency of fashion and clothing industry articles

This release was published on openPR.

Permanent link to this press release:

Copy

Please set a link in the press area of your homepage to this press release on openPR. openPR disclaims liability for any content contained in this release.

You can edit or delete your press release Salar Bil the predecessor of Tehran's conceptual - existence - challenges. here

News-ID: 3111253 • Views: …

More Releases for Butterfly

Global Butterfly Valves Market Restraints Analysis 2025

According to our (Global Info Research) latest study, the global Butterfly Valves market size was valued at US$ 4523 million in 2024 and is forecast to a readjusted size of USD 5821 million by 2031 with a CAGR of 3.7% during review period.

A butterfly valve is a valve that isolates or regulates the flow of a fluid. The closing mechanism is a disk that rotates.

Global butterfly valves main manufacturers include…

Double Offset Butterfly Valve Vs. Triple Offset Butterfly Valve: A Comprehensive …

In the field of industrial valves, butterfly valves are widely used in various industries such as oil and gas, water treatment, chemical processing, etc. Among the different types of butterfly valves, two variants take the lead: double eccentric butterfly valve and triple eccentric butterfly valve. In this comprehensive comparison, we will take a deep look at the design, advantages, disadvantages and applications of these two valves.

Image: https://cdn.globalso.com/zfavalve/double-offset-butterfly-valve-vs-triple-offset-butterfly-valve.jpg

Double Offset butterfly valve

As…

Butterfly Valve Parts' Names and Functions

A butterfly valve [https://www.zfavalve.com/butterfly-valve/] is a fluid control device. It uses a 1/4 turn rotation to control the flow of media in various processes. Knowing the materials and functions of the parts is vital. It helps to choose the right valve for a specific use. Each component, from the valve body to the valve stem, has a specific function. They are made of materials suitable for the application. They all…

Guest Post: Butterfly Needle Sets Market

Introduction

The butterfly needle set is a crucial medical device widely used for blood collection, intravenous (IV) therapy, and other procedures requiring short-term venous access. Known for its distinctive winged design, the butterfly needle is engineered for precision and ease of use, offering a more comfortable and controlled experience compared to traditional needles. These needle sets are particularly favored in pediatric, geriatric, and difficult-to-access veins, making them an essential tool in…

Butterfly Needle Sets Market: A Comprehensive Analysis

The butterfly needle set is a specialized medical device commonly used for drawing blood, administering medication, and providing intravenous access in various clinical and hospital settings. Known for its flexibility and ease of use, the butterfly needle set is an essential tool for healthcare professionals. This device is particularly preferred for patients with smaller veins or those requiring repeated venipuncture. As a result, the butterfly needle sets market has seen…

Why Choose The Handle Wafer Butterfly Valve

Firstly, in terms of execution, manual butterfly valves have many advantages:

Low cost, compared to electric and pneumatic butterfly valve [https://www.jinbinvalve.com/index.php?s=pneumatic+butterfly+valve&cat=490], manual butterfly valves have a simple structure, no complex electric or pneumatic devices, and are relatively inexpensive. The initial procurement cost is low, and maintenance is also relatively simple, with low maintenance costs.

Image: https://www.jinbinvalve.com/uploads/16ba3f0a.jpg

Easy to operate, no external power source required, can still operate normally in special situations such as…